Raphael Loewe: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

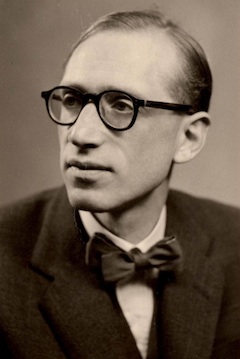

In Memoriam Professor

Raphael Loewe, 1919-2011

Written by: Ada Rapoport-Albert, Head of Department Hebrew and Jewish Studies, University College London

Raphael was born on 16 April 1919 in Calcutta, where his father was serving in the British army. He was educated at the Dragon School in Oxford and the Leys School in Cambridge, winning a major Classics scholarship to St John's College, Cambridge –the institution he regarded as his academic home and cherished to the end of his life. He was deeply moved when at the age of 90, in 2009, he was made an Honorary Fellow of the College.

In 1940 Raphael enlisted for war-time military service, and was posted as an intelligence officer to the Royal Armoured Corps in North Africa, where in 1943 he was awarded the Military Cross, granted in recognition of 'exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy'. He had apparently run through enemy fire to rescue the crew of a burning tank, and again risked his life to inform his commander of an impending enemy attack. He later served in the Italian front, where he was wounded, the injury leaving him with a permanent and pronounced limp.

With the war over, his first academic post was a Lectureship in Hebrew at Leeds. After spending a year as a Visiting Professor at Brown University in the USA, in 1961 he joined University College London's department of Hebrew, as it was then called, where he remained – eventually as Goldsmid Professor – until his retirement in 1984. He taught Classical Hebrew as Greek and Latin were still being taught at the time, transmitting to his students not only a passive knowledge of the language but the ability to compose in it, setting them weekly translation exercises from contemporary English poetry and prose into pure biblical Hebrew. This was an art of which he himself was a master, and he used it as an outlet for his own considerable literary talent. He translated prolifically both from and into the language, while also producing original compositions in the classicist idiom of Spain's medieval Hebrew poets, whose philosophical and aesthetic sensibilities, he felt, paralleled and thus were best rendered in the language of the seventeenth-century English metaphysical poets. He was particularly drawn to the eleventh-century Neoplatonist Solomon Ibn Gabirol, whose magisterial liturgical poem Keter Malkhut (Royal Crown) he translated into fully metered and rhymed English verse inspired by the sixteenth-century poet Edmund Spenser.

Raphael believed that the language of great literature, such as the English of the King James Bible (already archaic when published in 1611) or the Hebrew of Gabirol's poetry achieved its timeless, classical status precisely because it was not the vernacular of the authors. In contrast to most linguists who celebrate the 'revival' of Hebrew in modern times as an unrivalled success story, he lamented the re-vernacularization of the language, taking perverse pleasure in exposing its 'inauthentic', 'non-Semitic' grammatical and lexical features – the product of 'contamination' by European languages, above all Yiddish (a position which was long regarded as highly idiosyncratic, but which has recently gained some currency, largely under the impact of the controversial Hebrew bestseller Israeli – A Beautiful Language by linguist Ghil'ad Zuckermann, in whom Raphael came to see something of an ally). Raphael refused to recognize contemporary Modern Hebrew as a 'legitimate' language, but he could not resist the occasional challenge of submitting for publication in the Israeli press some of his Hebrew translations and essays. He would not allow editors to modify his Hebrew in any way that would compromise its 'organic' timelessness, with the result that on the few occasions when samples of his writings were published in Israel, readers were utterly bewildered by them. Even his virtuoso translation of Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyyat from Fitzgerald's nineteenth-century English version into the 'appropriate' medieval Hebrew verse, which was published in Jerusalem in 1982 and awarded a Tel-Aviv prize, remained a literary curiosity. On the other hand, he attracted an appreciative readership for his annotated English translations of medieval Hebrew poetry and rhymed prose, which accompanied several facsimile editions of illuminated manuscript versions of the Passover Haggadah, and appeared in his monograph on Ibn Gabirol as well as in his two-volume bilingual edition of Meshal Haqadmoni: Fables from the Distant Past by the thirteenth-century Spanish scholar and kabbalist Isaac Ibn Sahula. In 2010, near the end of his life, he published a large anthology of his poetic compositions and translations, many of which he had previously circulated in small doit-yourself bilingual brochures as New Year greetings to his colleagues and friends.

As a scholar Raphael produced insightful and erudite academic studies of various aspects of Hebrew culture, from Bible through classical rabbinic and medieval theology to Christian Hebraism, but translation was his passion and most constant creative occupation. At his instigation, a workshop for Hebrew translators was founded in London, meeting regularly for several decades at the home of the late Risa Domb, a former student who taught modern Hebrew literature at Cambridge. Raphael would bring to the meetings samples of translation not only from his beloved medieval poems but, from time to time, more whimsical experiments in prose, such as his Classical Hebrew version of Winnie the Pooh. On one occasion he read out his brilliantly witty English translation of a sardonic short story – Ger Tsedek (The Proselyte) – by Israeli Nobel-prize laureate S. Y. Agnon, perhaps the only modern Hebrew author whom Raphael was willing to admit into his canon of 'authentic' Hebrew literature.

Another life-long passion was the Spanish and Portuguese Jews' Congregation, of which Raphael was an active and devoted member (despite the Ashkenazi origins of his family), serving it in several senior capacities over many years. He passed away in London on 27 May 2011 to the sound of his favourite Sephardi liturgical melodies.

Reproduced by permission of the author obtained 03 May 2012.

Originally printed in the Annual Report 2010/2011 of the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies.