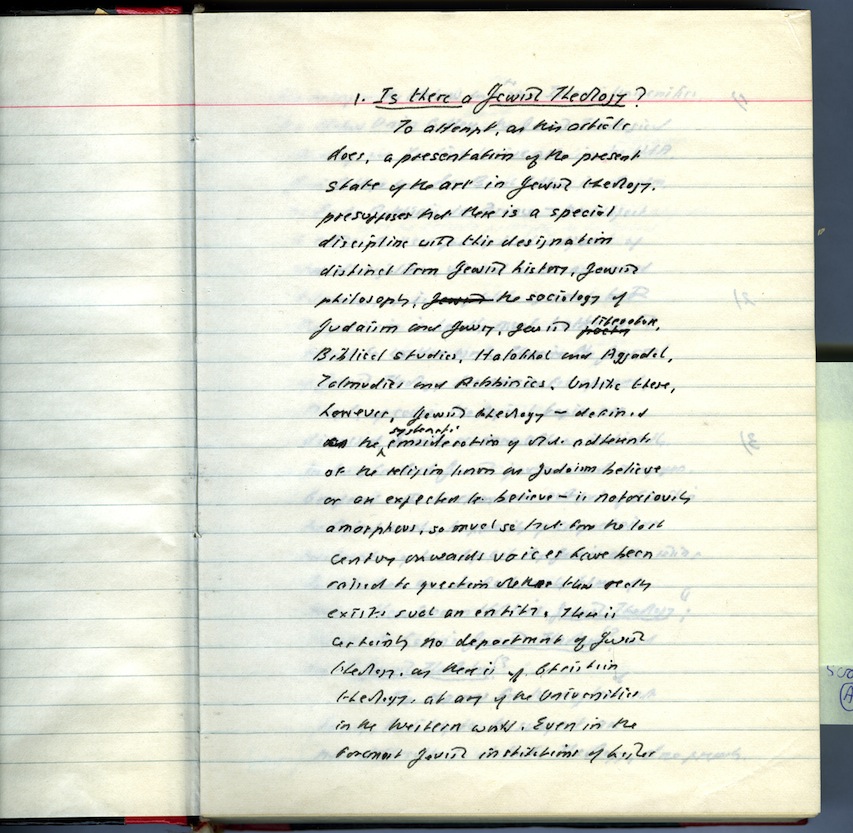

Jewish Status: Conversion and Marriage

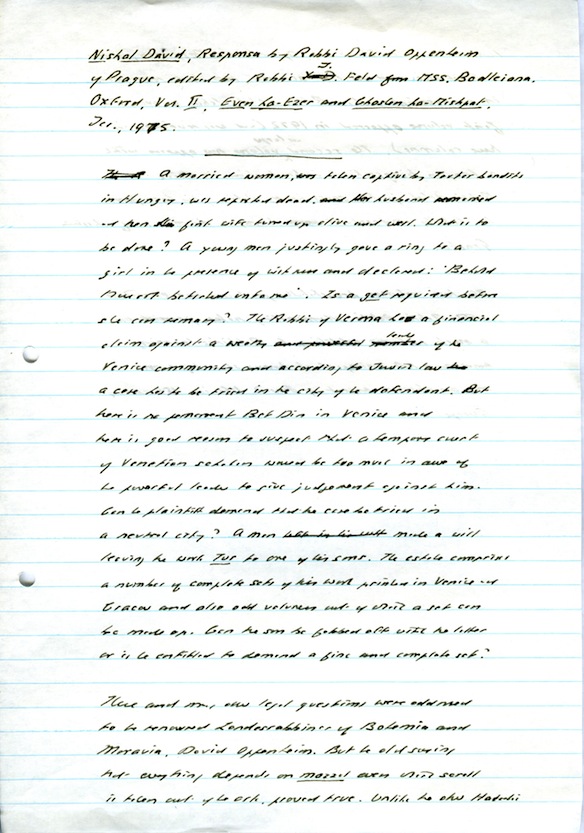

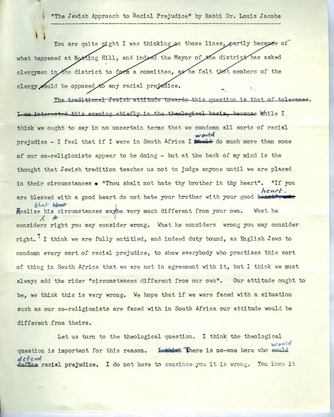

One lasting effect of the establishment of the Masorti movement has been the issue of Jewish Status: Are non-Orthodox marriages, conversions and any subsequent children considered to be ‘Jewish’ by the Orthodox movement? Regularly new stories emerge about families and individuals who consider themselves to be Jewish having this part of their identity challenged. Conversion (gerut) All forms of Anglo-Jewish Judaism accept conversions; however, the reasons for conversion, the process of conversion and the validity of the status of those converted in other synagogues is subject of much debate. Therefore in many ways the issues surrounding conversion are at the heart of the differences between the groups within the Anglo-Jewish community. For an Orthodox conversion to take place the person must undertake brit milah (male circumcision), be immersed in the mikveh (pool or bath of water), promise to keep the mitzvot (commandments), and undergo interview by the Beth Din. After this if all members of the Beth Din, lay and rabbinic agree that the person is genuine, they are given a Shtar gerut (Certificate of Conversion). The Halachically Orthodox communities in Britain will not accept those converted at any synagogue other than Orthodox Synagogues; therefore having a conversion certificate signed by someone approved by the Orthodox Synagogues becomes highly important. This is because the Orthodox Synagogues do not recognise non-orthodox Beth Din. Orthodoxy believes that the convert should make a promise to keep all 613 commandments (Taryag Mitzvot) if they are to become a Jew. Orthodoxy and progressive forms of Judaism differ on the value given to the mitzvot. For Orthodox Jews each commandment is of equal importance, whereas progressives consider some commandments to be no longer valid or to be less important, therefore they do not consider promising to keep all 613 commandments provides enough flexibility. Contrastingly, the Masorti movement accepts all conversions that it considers to have taken place halachically. John Rayner of the Liberal Jewish Synagogue in London in a sermon in 1996 said that ‘The progressives understand that the Orthodox authorities cannot accept their conversions, and don't hold it against them. But then they are not usually called upon to do so except in relatively rare cases in which a progressive proselyte, or a descendant in the female line of such a proselyte, seeks acceptance in Orthodox Judaism for a purpose such as marriage.

|

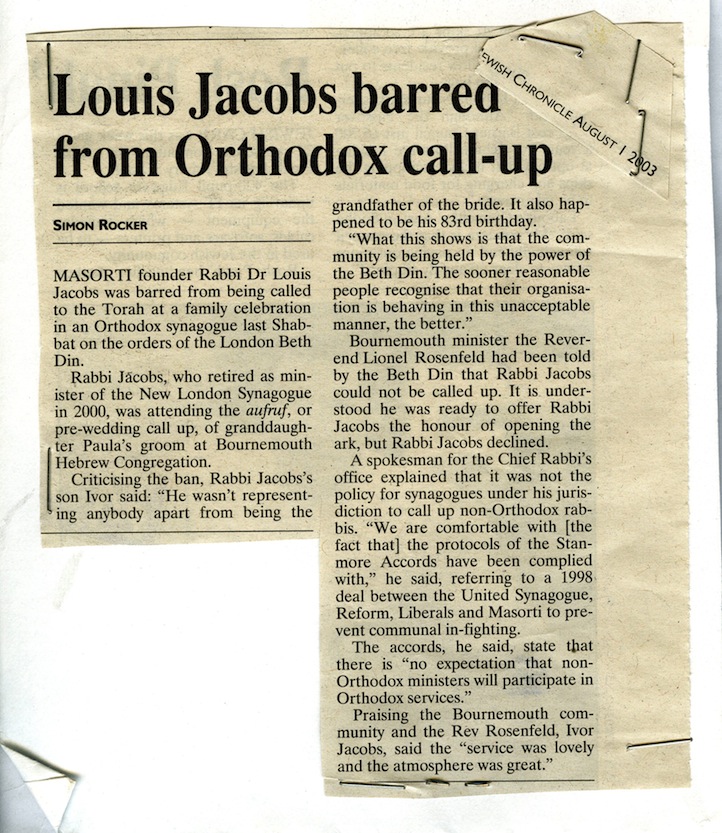

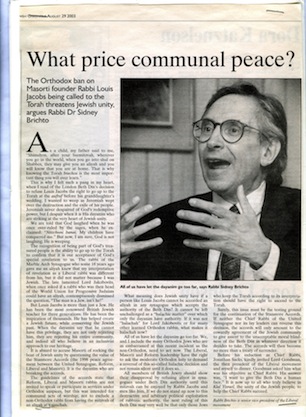

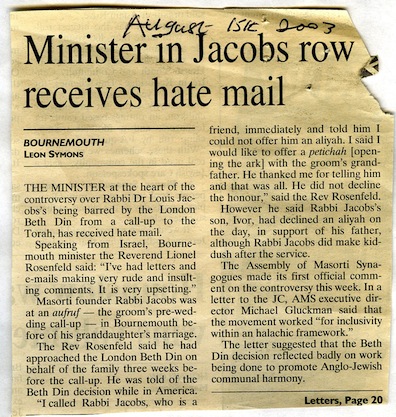

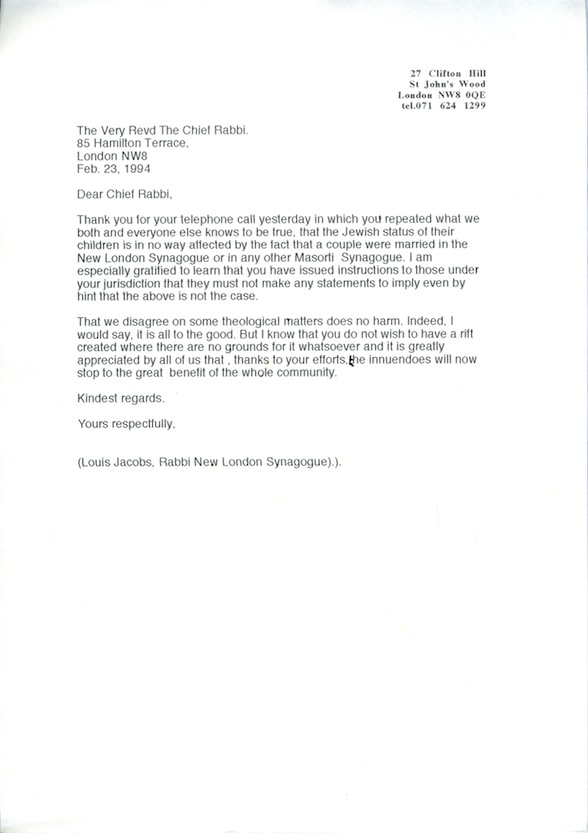

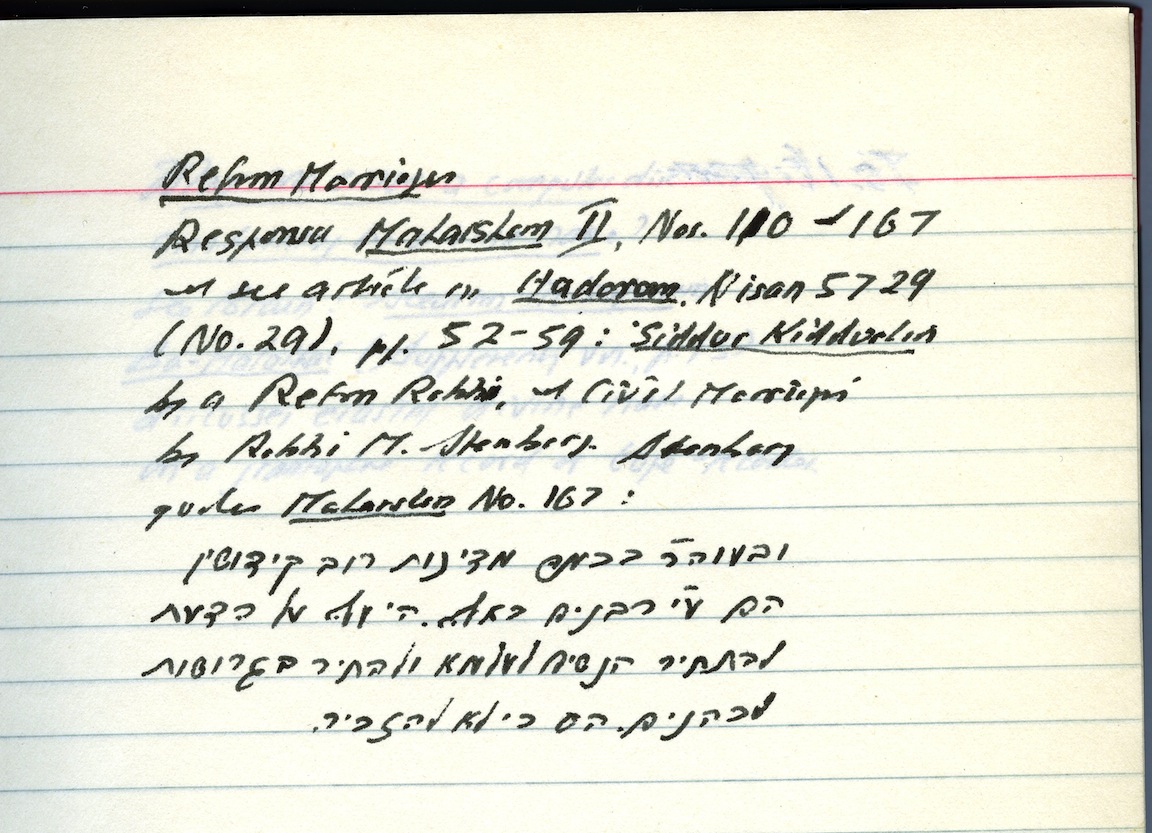

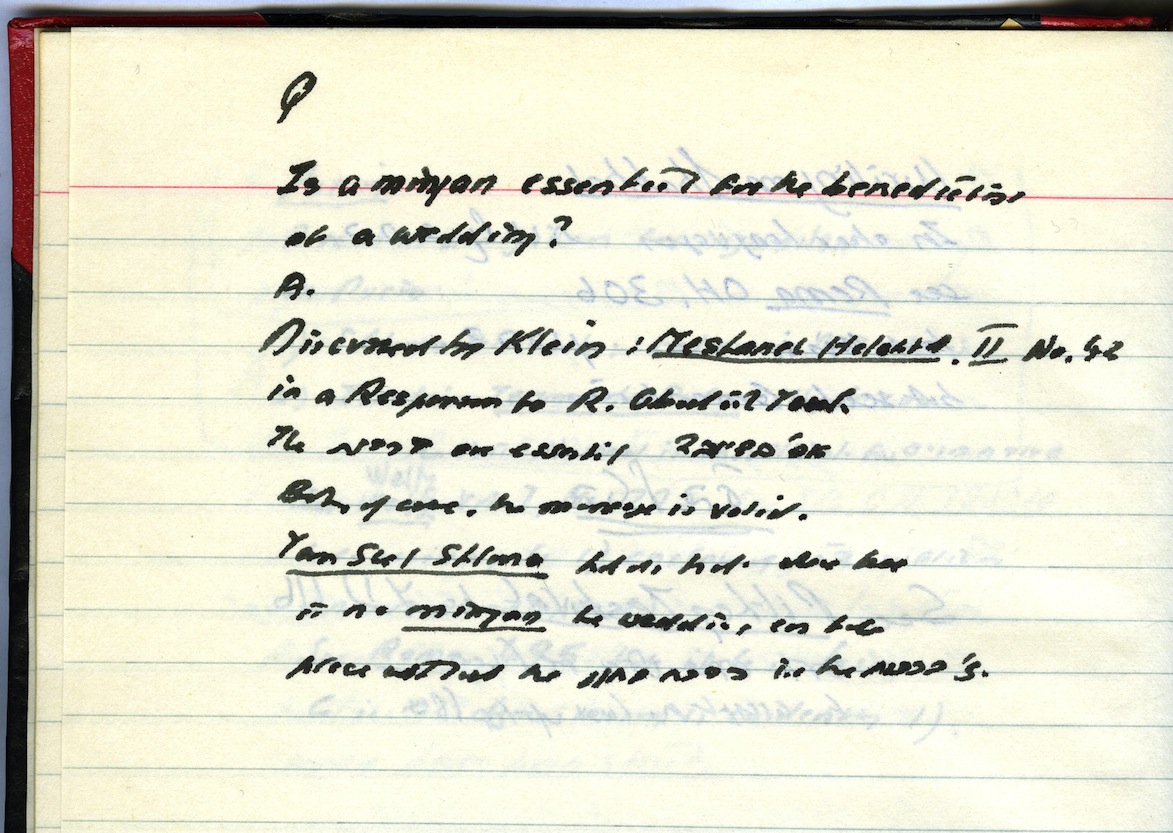

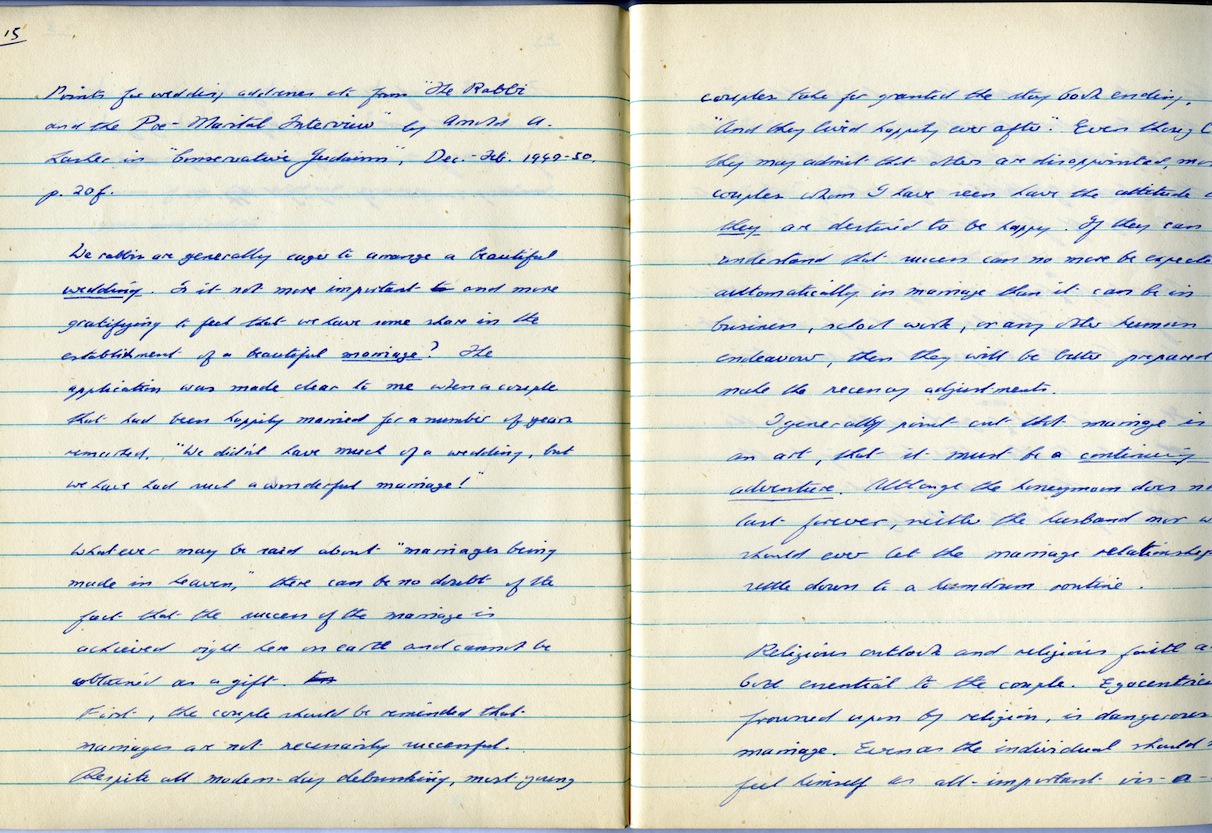

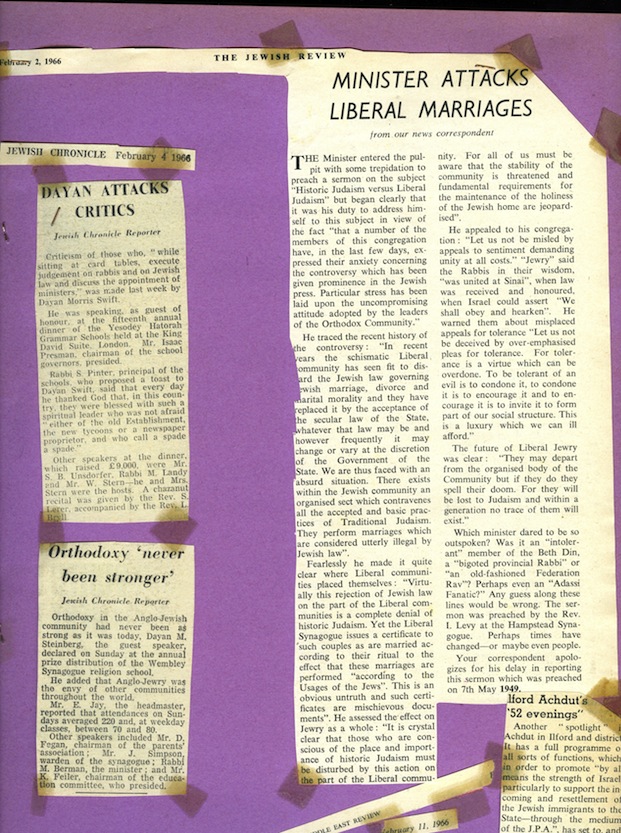

And in those cases, one would have thought, the Orthodox authorities would lean over backwards to regularize the applicant's status by their rules, with a minimum of fuss or difficulty’ (Endnote 1). In recent years there has been discussion about creating a Standardised Conversion. However this has never been agreed upon. Marriage However, children from marriages conducted in non-Orthodox synagogues are considered to be Jewish within Orthodoxy, if the marriage could have taken place in an Orthodox Synagogue (See H29d). The concern here is not about who officiates at the wedding, but the status of those getting married; whereas in conversion the key detail is under whom the conversion took place. However, non-Orthodox Rabbis, including Jacobs, are not permitted to officiate at weddings in Orthodox Synagogues in case it would be seen as an endorsement of their non-Orthodox beliefs (H67). In the personal archives of Louis Jacobs and amongst the published articles from the ‘Ask the Rabbi’ column, there are several examples of people seeking clarification as to their status or that of their children (H, 35, H,29). There are also examples of these in the Jewish press. In Jacobs' theology there are beliefs which he shares with the Orthodox movement. For example Louis Jacobs argues that a cohen cannot marry a divorcee, however Jacobs would bless others re-marrying after divorce (G, 99). During the 1960s the Jewish community appealed to parliament to permit Jewish marriage ceremonies to be conducted without a registrar present. This meant that the Jewish ceremony became accepted as a legal civil marriage, as well as a Jewish one.

(Endnote 1) John Rayner, ‘Counting the Commandments’, Not by Birth Alone: Conversion to Judaism, (eds) Walter Homolka, Walter Jacob, Esther Seidel (London & Washington: Cassell, 1997), pp. 98-99, 99.

PLEASE ALLOW 1-2 MINUTES FOR THE DOCUMENT SLIDESHOW TO LOAD

|