Snapshots of sample content from the Louis Jacobs Archive at the Leopold Muller Memorial Library

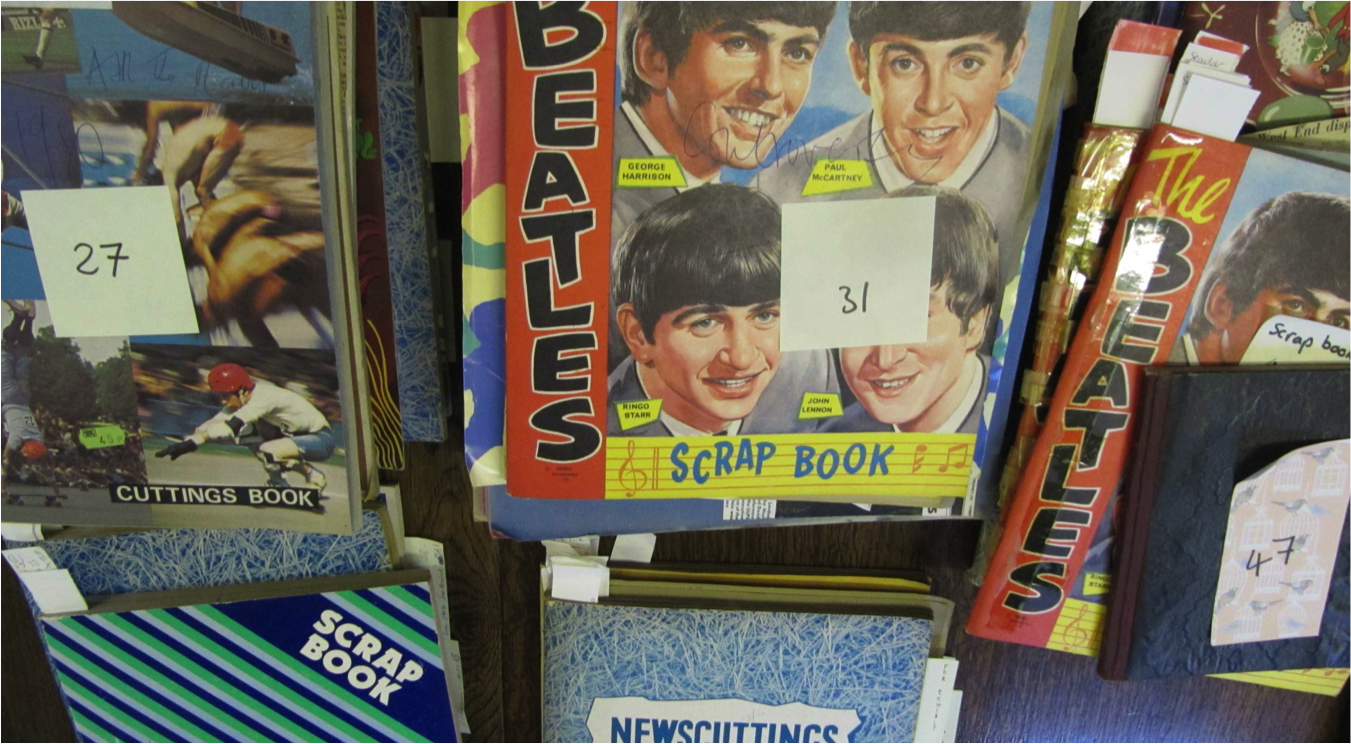

Photo 1.

Contents of the Jacobs Archive - preliminary analysis.

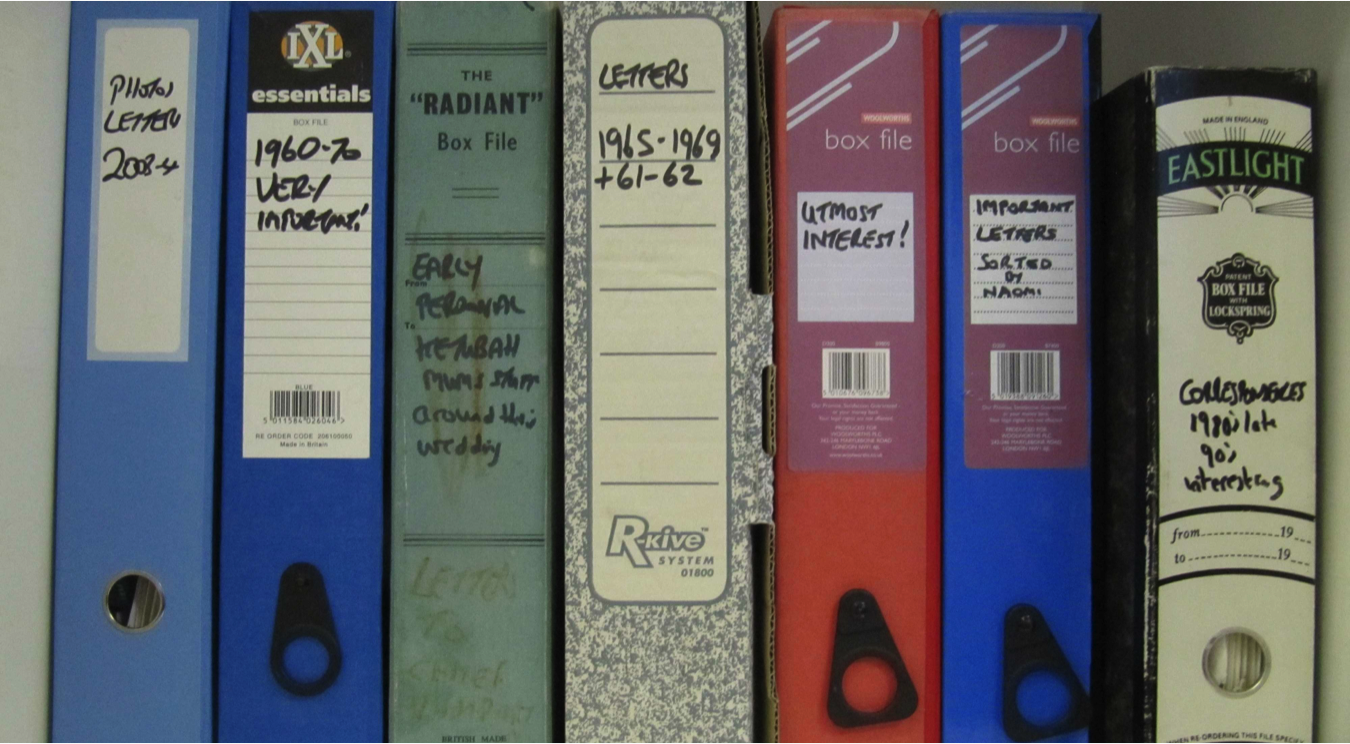

Photo 2.

Scrapbooks and notebooks - the key components of the Jacobs Archive.

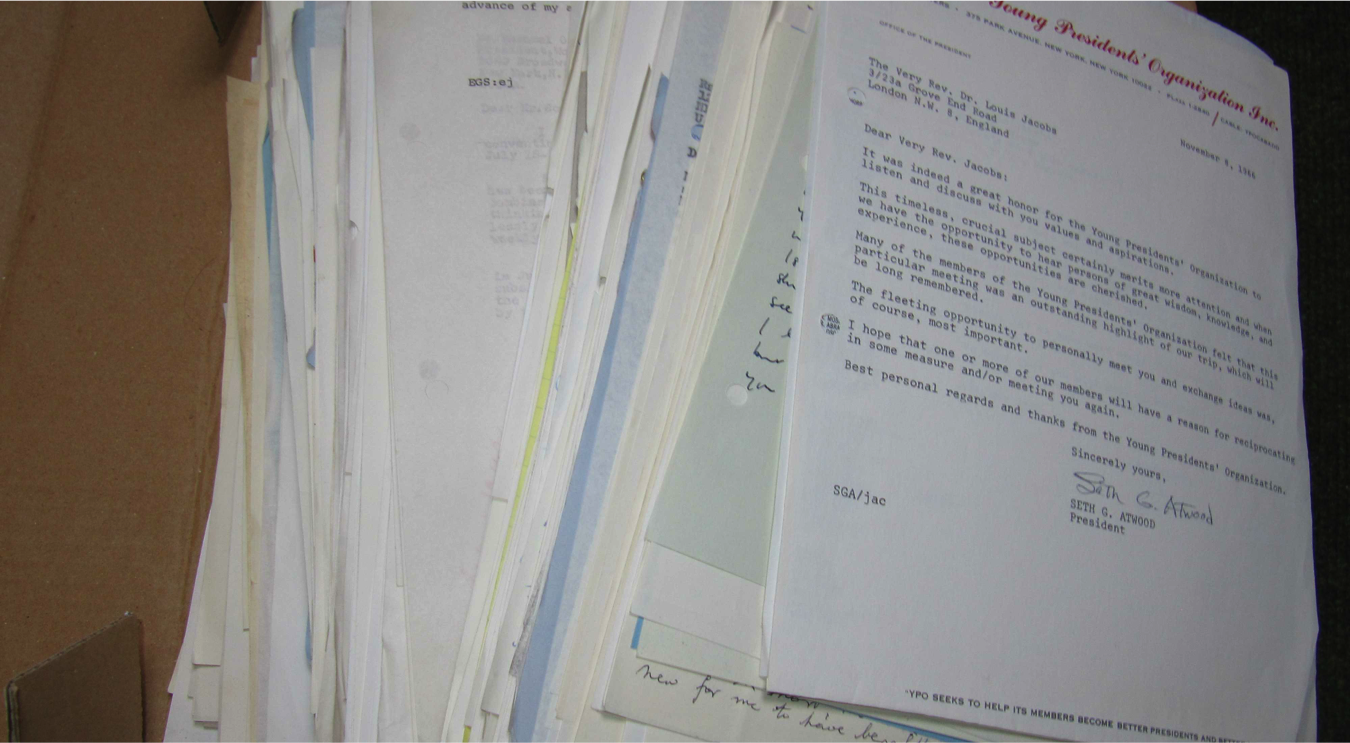

Photo 3.

Correspondence boxes.

Photo 4.

Sample selection of letters as stored in the correspondence boxes.

|

|

About the Louis Jacobs Archive

Rabbi Dr Louis Jacobs established over many years an extensive library and collated a large and wide-ranging archive. In 2006, shortly before he died, Louis Jacobs presented his personal library to the Leopold Muller Memorial Library, at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies. In 2013 the Centre’s OSAJS (Oxford Seminar in Advanced Jewish Studies) is researching Jewish Orthodoxy. To coincide with this project Louis Jacobs’ family loaned a significant part of Jacobs’ archive to the Muller Library.

For over fifty years, Louis Jacobs and his wife Shula collected personal and professional letters, copies of sermons, handwritten notes, newsletters and newspaper cuttings about Jacobs himself and on the Masorti movement.

The Library has been privileged to work on the archive for several months prior to the exhibition. Each of the items has been itemised and allocated a shelfmark; alongside the hand-list the archive is now a great resource and research tool. The Library has also undertaken the considerable task of digitising the loaned archive. Every single page has been scanned using quality equipment to produce high resolution images, some of which are available to browse on the website. This digitising process complements the work begun by www.LouisJacobs.org which also displays scans of parts of the archive, as well as transcripts of Jacobs’ key texts and sermons.

The Archive contains boxes of correspondence, with up to 450 items in each box, of which 1540 have been digitised by the Library staff. These letters are mostly written to Jacobs, but there are also drafts and copies of letters that he himself wrote. The correspondents include his personal friends and family, academic scholars at home and abroad in the fields of Jewish studies and theology, as well as letters from his congregants, other members of the Anglo-Jewish and international Jewish community as well as from other Jewish leaders and leaders of other faiths. These provide an insight not just into his range of contacts and interests, but they also highlight the vast demands that were put on him and his time.

Of particular importance for biographical and social research are the collections of family and community photographs, memorabilia and certificates: stored amongst pictures of Jacobs as a child are his CBE certificate and honorary degrees.

The other key components of Jacobs’ archive are the scrapbooks and notebooks. In Yarnton we currently have sixteen of Jacobs’ handwritten notebooks that contain sermon ideas, theological notes and reflections, as well as the original versions of many of his books. These notebooks are a real asset to the field of Jewish Studies and have been digitised, as well as being on display at the Library in Yarnton. It is interesting to compare the original texts and the published versions. Whilst these books tell us of Jacobs’ thought, the scrapbooks gather together and narrate the stories, voices and opinions of those around him.

The seventy-seven scrapbooks contain newspaper cuttings from around the world about Jacobs and the Jacobs affair right up until just before his death in 2006. They have been meticulously collated. There are some scrapbooks which only cover a few weeks, because the media attention at the time was so intensive. Although many of these articles are available elsewhere, this collection pulls together so much information, in such a systematic way, over an extended period of time, that it is possible to analyse shifts and changes in the response to Jacobs and Orthodoxy particularly amongst the Anglo-Jewish press. All of the archive material is available to consult in the Muller Library and forms the basis for the exhibition and its virtual counterpart. |